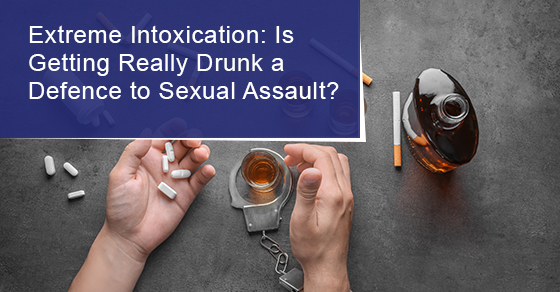

Extreme Intoxication: Is Getting Really Drunk a Defence to Sexual Assault?

Blog by Arun S. Maini

A man named Brown got drunk and consumed magic mushrooms. He lost his grip on reality and broke into two houses and attacked the occupants.

A man named Sullivan stabbed his mother after taking an overdose of prescription pills.

Another man named Chan also took magic mushrooms, and killed his father.

Did they do it? Yes.

Were they found guilty? No.

Why Not? Because in each case these defendants were not in control of their actions when they committed them. They were not even aware of what they were doing. They were each in a psychotic state brought about by ingesting drugs or a combination of drugs and alcohol. The name for this state of mind is called “automatism”.

A recent trilogy of cases by the Supreme Court of Canada has generated a lot of concern and commentary about this. Why? Because the Supreme Court found that a section of the Criminal Code prohibiting the defence of extreme intoxication was unconstitutional.

What is “extreme intoxication”?

Extreme intoxication is a legal term which refers to a mental state in which, as a result of the consumption of alcohol and/or drugs, a person becomes so impaired that their mental and physical abilities are compromised. This can impact whether they were physically or mentally able to commit the criminal act they are charged with. In most criminal cases where the defence of intoxication is raised, the issue is the mental state of the accused person. That mental state is impacted by intoxicants like alcohol or drugs. An intoxicated person will suffer from poor judgement, the lowering of inhibitions (i.e. they will often do things they wouldn’t do sober), and slower reflexes. They are also less able to process information, such as thinking through the consequences of certain behaviours. This inability to foresee the consequences of one’s actions plays a key role in criminal law.

There are three levels of intoxication recognized by the criminal law, of which extreme intoxication is the highest level. Only the two highest levels can be used as part of a defence of intoxication, as described in the next paragraph.

What is the defence of intoxication?

In criminal law, the defence of intoxication is a defence that claims that because of the consumption of drugs and/or alcohol, the defendant was so impaired at the time that he committed the criminal act that he should be found to be either not criminally responsible for the crime, or less criminally responsible than a sober person would be.

Whether the intoxication defence can work is a matter of degree. There are three levels of intoxication recognized in the criminal law:

- Mild intoxication

- Advanced intoxication

- Extreme intoxication.

Mild intoxication does not just mean you are feeling a buzz after a few drinks. It refers to the legal recognition, and scientific fact, that alcohol or drugs will impair your judgement and may encourage you to do things you normally would not do. Mild intoxication does not excuse criminal conduct. In some cases, one might argue that it reduces the level of criminal responsibility, but that is not an argument that carries much weight, because people are expected to know that if they get drunk or high, they may do things they regret later. Mild intoxication cannot be used as a defence to a criminal charge.

Advanced intoxication refers to a much higher and more severe level of impairment, in which a person will do things without being fully aware of them. Often people in a state of advanced intoxication experience blackouts and memory loss. However, even when they are extremely impaired, in the moment in which they commit a criminal act, they are able to do so consciously. The key is that they may not be aware of the full consequences of their actions. This can reduce the degree of their criminal responsibility (meaning a reduced sentence in some cases) but it does not excuse the defendant from criminal liability except in certain very limited situations, such as first or second degree murder.

Except in a very few situations, the inability to foresee the consequences of one’s actions does not excuse the criminal act. For example, if you get drunk and hit a pedestrian, it is not a defence that you did not intend to hit them or that you did not foresee the collision when you decided to have those extra drinks at the bar.

However, in a very small number of cases, such as first degree murder and second degree murder, the penalties are so severe that you can only be found guilty of these offences if you had the ability to foresee the potential consequences of the actions that led to the death of the victim.

To be found guilty of murder, you have to intend to kill the victim. The law of murder if very complicated but basically, if you intended to kill the victim, or you intentionally attacked them, knowing that this might result in their death, then you can be found guilty of murder. But in a state of advanced intoxication, you might not be able to form the intent to kill; and you might not be able to foresee the consequences of your actions.

In most situations, if you attack someone with a knife, you will be expected to know that this could easily lead to death. Similarly, if you load a gun and point it at someone, you can be expected to appreciate the risk of death you have created. But someone in a state of advanced intoxication may lack that awareness.

Having said that, however, each case depends on its own particular facts, and has to be approached with not only the science, but with common sense and experience. It is a very rare case for example, where one could load a gun and pull the trigger, and not be found to be aware that death might be the result of that action.

The other thing to keep in mind is that while you could be found Not Guilty of murder due to a state of advanced intoxication, you will not be acquitted and walk free. You would still be found guilty of manslaughter, which is one of the most serious offences in Canada, just below murder. That is because manslaughter does not have the same requirement that murder does of being able to foresee the consequences of one’s actions (I told you this area of law is complicated).

Extreme intoxication is a special case. It refers to a state of such impairment due to drugs and alcohol (alcohol is not enough, the science says that the intoxication would have to be drug-induced, or a combination of drugs and alcohol, not alcohol alone. A mental illness can aggravate the impact of the intoxicants. Extreme intoxication can induce a state of automatism (often referred to as “non-insane automatism” or “non mental disorder automatism”. Automatism is like a robotic state (sometimes referred to casually as sleep-walking) in which the person is completely unaware of what they are doing; unable to make decisions or act voluntarily; and, most crucially for the criminal law issue, to foresee the consequences of their actions.

If you commit a criminal act, but you are so impaired as to be unable to foresee the consequences of your actions, or even to be able to make a choice of whether to commit the act, then you are not criminally responsible for your action and you cannot be found guilty of the criminal offence.

What section of the Criminal Code did the Supreme Court strike down?

The Court found that s. 33.1 of the Criminal Code was unconstitutional. That section, which Parliament enacted in 1995, was designed to prevent acquittals in cases like the ones described above, where the defendant voluntarily consumed drugs and/or alcohol.

Why did the Court find this section to be unconstitutional?

It is a fundamental principle of justice that a defendant charged with a criminal offence cannot be found guilty unless he voluntarily committed a criminal act. There are three essential elements to this:

- The action committed must be illegal;

- The illegal act must have been committed by the defendant;

- The illegal act must have been committed voluntarily.

In each of the examples of brutal violence above, there was no question as to who committed the crimes. The issue was whether those crimes were committed voluntarily.

To be voluntary does not mean that they have to be pre-planned, well thought-out or even deliberate and willful. There are different degrees of intention recognized in law, and some of them, such as willful blindness and recklessness, do not require much intentional behaviour at all. But they all require at least some awareness of one’s actions or possible consequences.

In the case of someone whose brain is so distorted by intoxicants that they in effect suffer a complete break from reality, that degree of voluntary action or intent is missing.

Only intentional conduct can be punished by the state. If you are completely unaware of your actions or completely unable to control them, then you are not criminally responsible for that conduct. We see this in cases where some mentally ill defendants are found to be “not criminally responsible” on account of a mental disorder. In the old days, this was sometimes referred to as “not guilty by reason of insanity”.

Why does it matter if a crime was committed voluntarily or not?

It is a fundamental principle of law in Canada that punishment for a crime can only be imposed on someone who is criminally responsible for that crime. In other words, it is not enough that the suspect committed the crime. He has to be aware of it and have some ability to consciously decide to act. Just as the law says that you should not be punished for a crime you did not physically commit, the law also says that you should not be punished for a crime you are not mentally responsible for.

It seems unfair that someone can be found Not Guilty even if they killed or raped someone, when they voluntarily got drunk or stoned

True. The law often has to address very complex situations, where the competing interests are hard to reconcile. The victim of a crime seeks justice. The defendant who had no say in whether to commit the crime or not likewise does not deserve to be punished for it.

It can be very hard to hear about tragic situations that scream for someone to be held responsible.

But there are different degrees of responsibility, from planned and deliberate conduct, to accidental or involuntary conduct. And someone who commits an act that results in a terrible outcome should not always be held legally responsible for every consequence of that act.

For example, should a driver who turns his head in the direction of a distracting noise or movement, and who then hits and kills a pedestrian, be held as responsible as someone who deliberately drove into that pedestrian?

What about a person who smuggles a deadly drug like fentanyl into Canada because back home a local gang has threatened to kill his wife and children if he refuses? Is he as responsible as the commercial trafficker?

It is true that someone who chooses to drink or take drugs should bear some responsibility for the consequences of that conduct. Drinking and driving laws are a good example of that. If you get behind the wheel when you are drunk, you will be held accountable for the consequences if you get into a collision, or get pulled over by police, because you are creating a foreseeable risk of harm to others. Someone who takes street drugs at a party to get high and feel good is not even beginning to contemplate that because the drugs might be spiked, or might react adversely with his neural pathways, that he might break into a home and rape someone. Yet there is a good argument to be made that when you consume an intoxicating substance, you are aware that you are giving up a measure of control over your inhibitions and your judgment. But does that mean that you should be responsible for all consequences of that behaviour, no matter how remote they are from your original intention of simply having a good time at the party?

These issues are moral ones, philosophical ones that delineate the choices a society makes when it comes to its most basic values. And these interests often overlap or even conflict. And that is why they are so difficult.

Does all this mean that being drunk can be a defence to rape and murder?

No. The Supreme Court has made it clear that this decision does not change the law. It is not a defence to a criminal charge to say that you were drunk. “Extreme intoxication” is not the same as being drunk, or being high. Extreme intoxication is a state way beyond being extremely drunk or stoned. It is a separate mental state altogether, known as automatism.

Automatism is extremely rare. As far as science can tell, it cannot arise from drunkenness alone. It requires drugs, mental illness or a combination of both. Alcohol can add to that mental state, but alcohol alone is not enough.

Automatism is very difficult to prove. It requires the expert evidence of psychiatrists or psychologists who are held to a very high standard. It only in the rarest of cases that a defence like this will succeed, and when you consider the harm that was caused by actions like the ones described at the beginning of this article, you can see why.

So what happens next? Can Parliament find a solution?

It is essential in a free and democratic society like Canada that the law respect the rights and freedoms of its citizens. Sometimes that means that laws that infringe on those rights and freedoms need to be corrected from time to time. The Supreme Court made it clear that this decision was not the last word on criminal responsibility. Parliament can find another solution that does not let someone who commits a horrific act that injures or kills others “get away with it”. But such a law has to respect those fundamental principles.

Difficult choices like this are left to elected members of Parliament to decide. And the courts only intervene when those choices infringe unacceptably on the fundamental rights and freedoms set out in the Charter of Rights. It is a delicate balance, and one which requires sensitivity, flexibility and empathy. Difficult choices will not please everyone, which is why in order to avoid undermining the trust and respect that Canadians have for an institution like the Supreme Court, their decisions should be rational, clear and easy to understand. That is often a very delicate balance to achieve.

If you or a loved one are facing criminal charges and need the advice of an experienced and skilled lawyer to help you through the legal process, contact The Defence Group for a free consultation at 877-295-2830 or at www.defencegroup.ca .

Arun S. Maini is a criminal lawyer and former prosecutor with over 25 years of experience